Mongabay.com | Rhett A. Butler

Mongabay.com | Rhett A. Butler

Over the past twenty years Brazil emerged as an agricultural superpower: today it is the largest exporter beef, sugar, coffee, and orange juice, and the second largest producer of soybeans.

While much of this growth has been fueled by a sharp increase in productivity resulting from improved breeding stock and technological innovation, Brazil has benefited from large expanses of available land in the Amazon and the cerrado, a grassland ecosystem. But agricultural growth in Brazil has always been limited — at least on paper — by its environmental laws. Under the country’s Forest Code, landowners in the Amazon must keep 80 percent of their land forested. In the cerrado, the proportion is 20-35 percent.

The provisions of the Forest Code make Brazil’s environmental laws some of the most stringent in the world, but in practice they are haphazardly enforced and often used as a tool for extracting bribes from farmers and ranchers, rather than protecting the environment. As such, it is estimated that less than 10 percent of landowners in the Amazon are compliant with the regulation.

Given widespread “illegality” in the farm sector, there is strong interest in “regularizing” the Forest Code. Leading the push has been an alliance of large-scale farmers and ranchers, which is hoping to reduce forest reserve requirements, stipulations for reforestation, and restrictions against clearing forest along waterways and on hillsides.

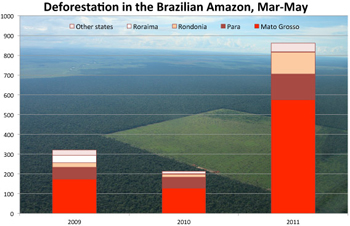

But the effort to reform the Forest Code is controversial. Citing Brazil’s progress in reducing its annual deforestation by more than 75 percent since 2004, environmentalists generally oppose the proposed changes. Some greens fear the new code would effectively grant “amnesty” for illegal deforesters and signal that further transgressions may be forgiven in the future, potentially reversing Brazil’s progress in arresting deforestation. Recent data released by Brazilian NGOs and the government seems to support these concerns, revealing a sharp increase in deforestation and degradation in key agricultural states. Two-thirds of clearing in recent months occurred on private lands, which are most likely to benefit from changes in the Forest Code.

But the effort to reform the Forest Code is controversial. Citing Brazil’s progress in reducing its annual deforestation by more than 75 percent since 2004, environmentalists generally oppose the proposed changes. Some greens fear the new code would effectively grant “amnesty” for illegal deforesters and signal that further transgressions may be forgiven in the future, potentially reversing Brazil’s progress in arresting deforestation. Recent data released by Brazilian NGOs and the government seems to support these concerns, revealing a sharp increase in deforestation and degradation in key agricultural states. Two-thirds of clearing in recent months occurred on private lands, which are most likely to benefit from changes in the Forest Code.

Agroindustrial interests in Brazil maintain that modernization of the 1965 law is critical to encouraging investment in the farm sector and providing more food to feed the world. They note that farmers and ranchers in places in the United States and Europe face no legal reserve requirement.

Among the biggest supporters of the Forest Code reform bill is Senator Katia Abreu, a member of opposition Democrat Party who heads the Brazilian Agricultural Confederation (CNA).

Abreu, herself a large landowner in the state of Tocantins, told mongabay.com during a June 2011 interview that reform of the Forest Code is essential to ensuring Brazil’s economic growth, while safeguarding environmental services provided by the Amazon rainforest.

“To become a global agricultural powerhouse, Brazil needs modern environmental legislation, which combines agricultural production and environmental conservation, providing a legal certainty for farmers, who depend on a balanced environment to continue production,” she said.

“The Brazilian Forest Code is a law from 1965, modified by a series of government actions, which no longer reflects the reality of national agriculture. If not updated, will continue criminalizing 90% of farmers in the country.”

Abreu claims modernization of the Forest Code “will not diminish the rules of protection.” Instead, the rules will “become clearer.” Abreu maintains the product of reform will be a “preserved” Amazon: “In 2030, the Amazon will be is as it stands today, preserved.”

INTERVIEW WITH THE PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERATION OF AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK OF BRAZIL (CNA), SENATOR KATIA ABREU

INTERVIEW WITH THE PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERATION OF AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK OF BRAZIL (CNA), SENATOR KATIA ABREU

Mongabay: What inspired you to enter politics?

Senator Katia Abreu: I became involved in politics in order to find solutions for farmers and people in the rural areas of my state, Tocantins, in Brazil. I first began by serving as president of the Rural Union City Gurupi, located in a farming region which had a very weak infrastructure. I identified the challenges the area faced and sought the most efficient solutions for them. Following this work, I chaired for four consecutive terms in the Federation of Agriculture and Livestock of Tocantins. The defense of rural activity continued to be my focus, when, at that time, I was elected as representative in House.

Between 2000 and 2001, I chaired the so-called “caucus” – a group of representatives in the House who defends the interests of farmers. I worked hard for the Brazilian countryside and my state. In 2002, I returned to the House as the most voted representative of Tocantins, with 76,000 votes (13% of the votes in the state). In 2005 I was elected Vice Chairman of the Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock in Brazil (CNA), when I deepened my knowledge and established a working strategy to ensure optimal conditions of production for the agricultural sector. In 2006, I became a Tocantins Senator. I chaired the CNA in 2008, when I was able to work on actions in defense of a sector that generates one third of Brazilian GDP, 42% of exports and one third of the jobs in the country.

Mongabay: In your opinion, why has Brazil become an agricultural superpower? What is stopping Brazil from becoming an even bigger agricultural giant?

Senator Katia Abreu: Producing grains and meats is one of Brazil’s strengths, which is in a position to meet the growing domestic and foreign demand for food, without compromising the preservation of 61% of the country’s 851 million hectares which are still covered by native vegetation. Brazil is very efficient in the farming sector. The productivity of agriculture increased by 151% between 1976 and 2011, while the area planted increased by only 31% in the same period. However, the growth of the sector is being stalled because of the legal uncertainty of labor laws, environmental and health regulations and the lack of agricultural policy updates. In order that the country becomes a global agricultural powerhouse, we must prioritize improvements to our inadequate infrastructure, as it is the main obstacle to agricultural production and reduces the competitiveness of Brazilian products in foreign markets.

Mongabay: Why do you think that the reform of the Forestry Code is required? In your opinion, what are the most important changes?

Senator Katia Abreu: The Brazilian Forest Code is a law from 1965, modified by a series of government actions, which no longer reflects the reality of national agriculture. If not updated, will continue criminalizing 90% of farmers in the country. To become a global agricultural powerhouse, Brazil needs modern environmental legislation, which combines agricultural production and environmental conservation, providing a legal certainty for farmers, who depend on a balanced environment to continue production. The new legal framework – approved in the House of Representatives (410 votes in favor and 63 against) and now goes to the Senate – is to balance these two issues, while imposing in Brazil strict environmental laws, including the requirement of preserving 20% to 80% of areas with native vegetation (mostly forest) as a legal reserve within private property, a demand that exists nowhere else on the planet.

The main points of the new Forest Code are the settlement of properties and the rescue of environmental liabilities, correcting oversights which occurred during the occupation of production areas, because it will allow the settlement of farmers in the country and the consolidation of areas which were cleared before July 2008.

To read the rest of the interview visit: Mongabay.com